“Oh, I’m not creative.”

How often have you heard a colleague or friend deny their innate gift?

We are all born creative; then some go to great lengths to defuse their capability. As Seth Godin noted, much of American public schooling has had a sly purpose in curtailing creative potential—the better to fashion useful, obedient workers.

With the act of creating being so ingrained in human behavior, it might seem odd to question precisely how we do it. Don’t we just do it? But I wonder—what are the mechanisms, the processes, fuels, ingredients, adjuvants, and conditions which might incite “better” creative outcomes? Perhaps, like me, you’ve birthed an idea and stopped to ponder just how exactly the miracle occurred.

Fortunately, these questions began to have more nuanced answers in 1975.

The creative act is not for the faint of heart

How did Michelangelo, Emily Dickinson, Bill Bernbach, Amy Winehouse, or Henri Poincaré unearth their remarkable concepts? How does our black box function, and can its output be improved?

It might help to begin with a definition. “When we define creativity,” writes Psychologist Dr. Rollo May in The Courage to Create (Amazon, Goodreads), “we must make the distinction between its pseudo forms on the one hand—that is, creativity as a superficial aestheticism. And, on the other, its authentic form—that is, the process of bringing something new into being.”

Bringing something authentic to life requires a journey into the fog. In creating something new, May states:

“We are called upon to … confront a no man’s land, to push into a forest where there are no well-worn paths and from which no one has returned to guide us. This is what the existentialists call the anxiety of nothingness. To live into the future means to leap into the unknown, and this requires a degree of courage for which there is no immediate precedent and which few people realize.”

To create, to be an ideas person, is to harness courage. (This newsletter gets part of its title from May’s work.) Why is courage so necessary? As the quote above makes clear, creating something entirely new comes with a degree (or many more) of inherent anxiety. Creativity is an encounter, whether you like it or not, asserts May. One we may not be fully prepared to attend. This experience, this journey, says May, is “characterized by an intensity of awareness, a heightened consciousness.” He continues:

“Artists encounter the landscape they propose to paint they look at it, observe it from this angle and that. They are, as we say, absorbed in it. Or, in the case of abstract painters, the encounter may be with an idea, an inner vision, that in turn may be led off by the brilliant colors on the palette or the inviting rough whiteness of the canvas. The paint, the canvas, and the other materials then become a secondary part of this encounter; they are the language of it, the media, as we rightly put it. Or scientists confront their experiment, their laboratory task, in a similar situation or encounter.

The encounter may or may not involve voluntary effort—that is, ‘will power.’ A healthy child’s play, for example, also has the essential features of encounter, and we know it is one of the important prototypes of adult creativity. The essential point is not the presence or absence of voluntary effort, but the degree of absorption, the degree of intensity (which we shall deal with in detail later); there must be a specific quality of engagement.”

To engage in creativity is to risk—something, everything. To engage is to reject the status quo, to stand apart from safe concepts and opinions. In this context you can begin to empathize with the many who taught themselves to be “not creative.” In this context courage becomes absolutely necessary.

Yet these engagements or encounters are no mere happenstance. Creativity isn’t luck. It is typically very hard, diligent work. May goes to great lengths in defining the effort required to reveal a remarkable insight.

“Unconscious insights or answers to problems that come in reverie do not come hit or miss. They may indeed occur at times of relaxation, or in fantasy, or at other times when we alternate play with work. But what is entirely clear is that they pertain to those areas in which the person consciously has worked laboriously and with dedication.”

There’s an infamous story of the French mathematician Henri Poincaré having an idea. “At the moment when I put my foot on the step,” recalls Poincaré, “the idea came to me, without anything in my former thoughts seeming to have paved the way for it.” Much more is illuminated both before, during and after in the mathematician’s telling. But thanks to May’s gifts, this anecdote has been deconstructed to reveal some of the mystery we perceive inside the idea-making machinery.

“[Poincaré] sees the characteristics of the experience as follows:

(1) the suddenness of the illumination;

(2) that the insight may occur, and to some extent must occur, against what one has clung to consciously in one’s theories;

(3) the vividness of the incident and the whole scene that surrounds it;

(4) the brevity and conciseness of the insight, along with the experience of immediate certainty. Continuing with the practical conditions which he cites as necessary for this experience are

(5) hard work on the topic prior to the breakthrough;

(6) a rest, in which the ‘unconscious work’ has been given a chance to proceed on its own and after which the breakthrough may occur (which is a special case of the more general point);

(7) the necessity of alternating work and relaxation, with the insight often coming at the moment of the break between the two, or at least within the break.”

I’ve returned to Courage to Create many times, seeking solace, seeking confidence. May’s writing has had a profound impact on my own creativity, especially when trying to teach it. His work established a foundation upon which further research and other writers built keen insights we continue to leverage.

Published in 1975, The Courage to Create appeared at a time when psychology was undergoing remarkable transformation. As May observed, “When we examine the studies and writings on creativity over the past fifty years, the first thing that strikes us is the general paucity of material and the inadequacy of the work …[creativity] was generally avoided as un-scientific, mysterious, disturbing, and too corruptive of the scientific training of graduate students.”

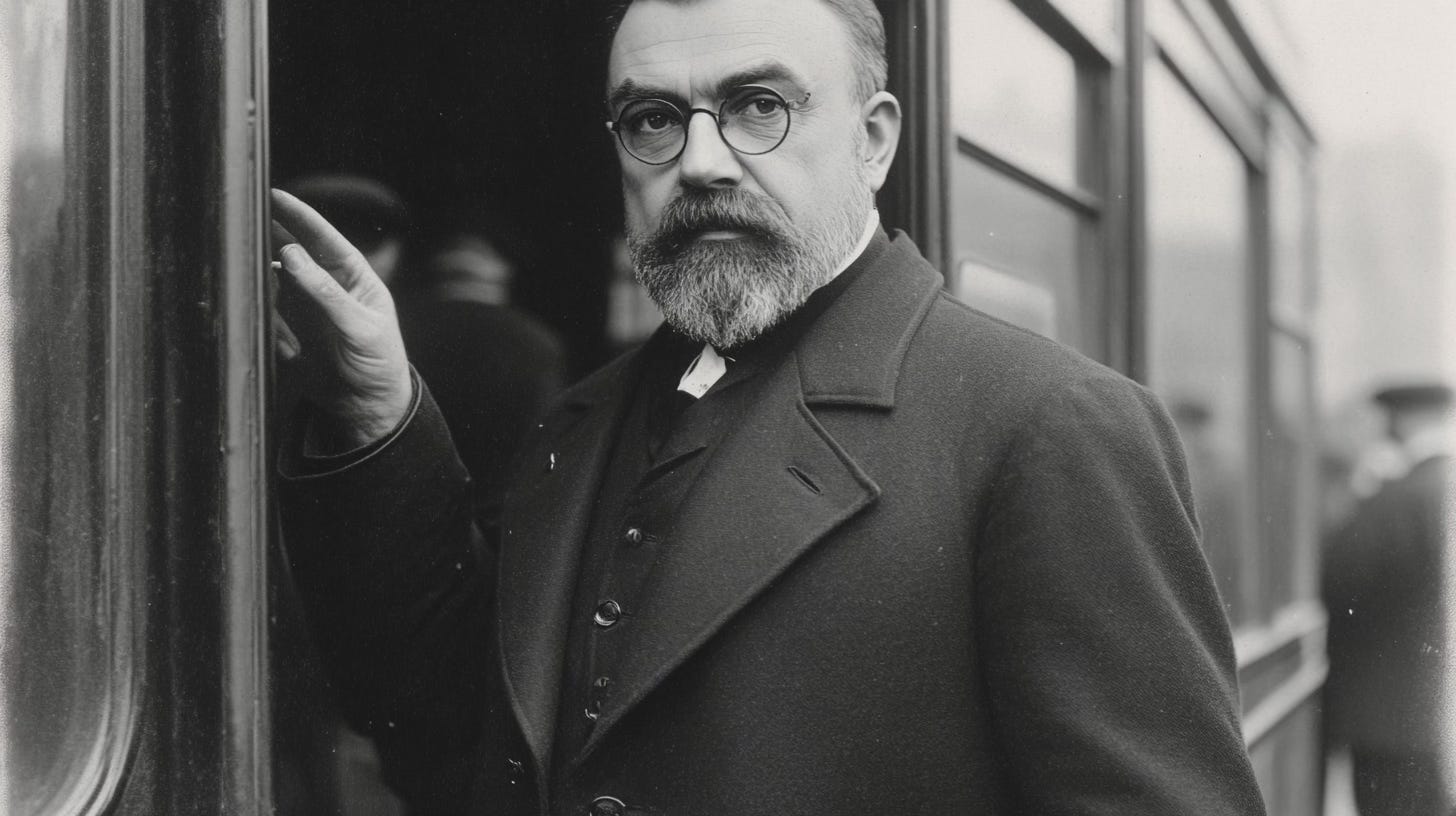

Dr. Rollo May (1909-1994) is known for his work as a practicing psychologist, writer and lecturer. He focused primarily on existential psychology, teaching at Harvard, Princeton and Yale and was Regents’ Professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He also served as a training and supervisory analyst at the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Psychology. In addition to The Courage to Create, May’s publishing includes The Meaning of Anxiety, Man’s Search for Himself, and the national bestseller Love and Will.

His life and work are encapsulated here.

AI+Creativity Update

🤖🍎 Later today Apple will, in theory, reveal what AI, or Apple Intelligence, means in practical reality. It’s billed as the iPhone 16 launch but within that context is the story of how Cupertino plans to roll out its approach to artificial intelligence on device, and at scale. More from CNN, USA Today, and MacRumors.

🤖⚙️ EverArt is, “the first full-stack AI tool that makes it easy to fine-tune AI on your brand. You can finally generate images of your products and branding imagery with production-level accuracy.” Maybe? It’s what brands say they want.

🤖📣 Icon does two things: First, they help you curate and hire influencers. Second, they use AI to convert a single influencer video into…many. It’s the same theory as HeyGen. Once you’ve got a video, it serves as the training data for subsequent generated videos.

🤖😳 Bytedance and Zhejiang University have published research for Loopy, an AI which can, “generate vivid motion details from audio alone, such as non-speech movements like sighing, emotion-driven eyebrow and eye movements, and natural head movements.”

🏊🏼♀️🏀 The Paralympics just wrapped up. If you struggled to comprehend how athletes with different disabilities competed fairly, check out Le Monde’s useful explainer of the ranking process.